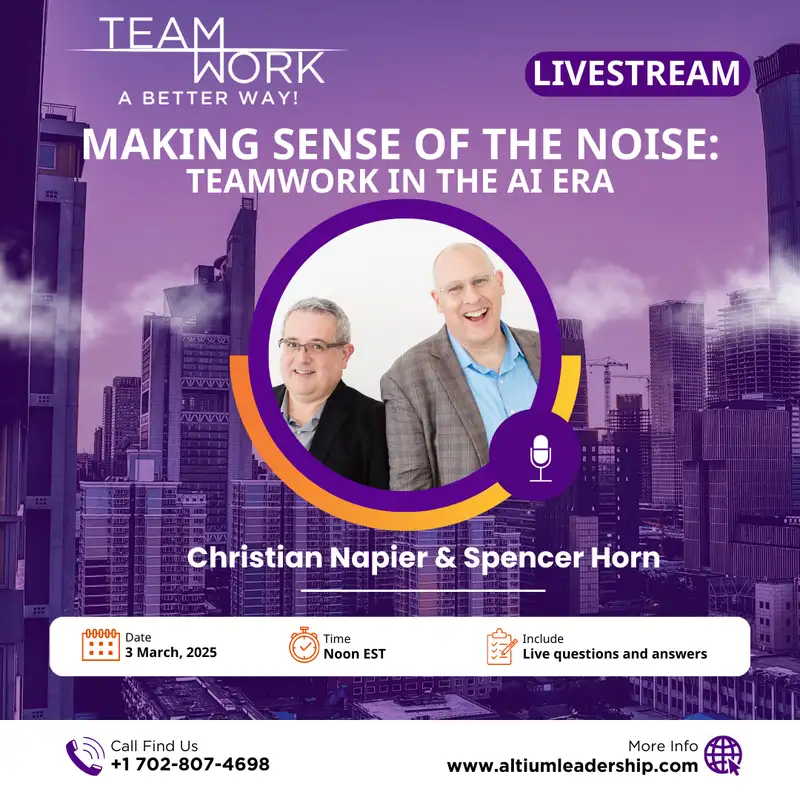

Making Sense of the Noise: Teamwork in the AI Era

Christian Napier

00:13 - 00:25

Happy Monday, everyone. Welcome to another episode of Teamwork a Better Way. I'm Christian Apier, and I am joined by our very technologically astute co-host, Spencer Horn. Spencer, how are you?

Spencer Horn

00:26 - 01:06

Oh, I'm flummoxed. I totally messed up. We had, through Ecamm, I pressed a button and it went live, and then I panicked, and I canceled it, and now I can't find the old link. Everything that we set up on on LinkedIn and other Facebook and restream is is all messed up right now and so people may not be able to find this the show and and There you go. I am definitely technologically challenged. And here we are talking about, you know, making sense of the noise in the age of AI, the era of AI, which I'm really excited, Christian, to talk about this.

Spencer Horn

01:06 - 01:07

I'm really

Christian Napier

01:07 - 01:24

excited too. You're not the only one technologically challenged. I'm facing the same situation right now. I'm having to work off another laptop because my laptop that I usually use for these podcasts is having some issues, and I didn't have time to get all those resolved, and so I'm coming to you from

Spencer Horn

01:24 - 01:24

another

Christian Napier

01:25 - 01:40

laptop, and it's camera, which is not great, and it's microphone, which is not great, and my lighting, which is kind of weird with this camera. So, hey man, you know, March, in like a lion. And it's

Spencer Horn

01:40 - 01:58

real. I mean, here we are. We've got the challenges that we get to talk about. So I really wanted to talk about this topic, Christian, just because of your expertise in AI. You know, you're the director of AI and technology for the state of Utah. I'm sure that's not the exact title. You correct me?

Christian Napier

02:00 - 02:05

Oh, that's good. Although I'm not here as representing that title, but...

Spencer Horn

02:05 - 02:08

No, no, I know you're not, but just in terms of credibility and credentials.

Christian Napier

02:08 - 02:12

But in terms of credential, yes, I do serve in that

Spencer Horn

02:12 - 02:40

role. Yeah, and I know you're not representing the state, forgive me, but I know that you are somebody that I have known for over 20 years. And when we first started working together, you were bringing solutions for technology over 20 years ago to a company that we were both part of. I remember going on the road with you and trying to promote these technological training devices that you helped us develop. Do you remember that?

Christian Napier

02:41 - 03:26

Yeah, that was a long time ago. Wow, it was 20 years ago. We were trying to do that to help people learn English in different industries, and we had engineered a fit-for-purpose workstation that would help people do that within their work environment rather than have to go out to an environment where they would have a PC or a laptop available, but actually learn in their working environment. That was 20 years ago, and it was a lot of fun. And here we are now in this area of generative AI, which is creating all the buzz right now in technology.

Christian Napier

03:27 - 03:37

But it's not a perfect technology by any means, and it's causing a lot of issues. So we'll kind of talk through those in our conversation today.

Spencer Horn

03:38 - 04:28

Absolutely. So I found an article that I want to share with our listeners on Forbes and talk a little bit about that. And so I'm going to It kind of set us up here. The author was talking about how we are awash in information today, and it's really true. Basically, we have created so much information and knowledge that it's hard to actually understand what is the information that's useful to us and if the information is actually correct. And we keep hearing this word, misinformation, and it's something that is thrown around a lot because reality seems like it's no longer fixed.

Spencer Horn

04:28 - 05:19

People interpret information so differently. And one of the challenges that we have is we have all of this information that's out there, which people are interpreting based on their perspectives and their beliefs and their ideas. And we're not really getting, we live in what they call what the post-truth era. And what does that mean? It means we're not looking for absolute truth anymore. We're looking for narratives that fit our beliefs and our ideas about how the world should work. And so we live in echo chambers, if you will, because if I have a perspective that I believe in, I am going to find research and information that supports those biases that I have, and that's done on all sides.

Spencer Horn

05:20 - 05:22

What's the problem with that, Christian?

Christian Napier

05:23 - 06:01

Well, the problem with that is that you're intentionally leaving out key information that could lead you to different outcomes. And so, You know, kind of bringing it back to teams, what that means is that we may make suboptimal decisions in our organizations because we're willingly or unwillingly limiting the picture that we see. We have a difficult time seeing things as they really are, and we focus more on seeing things as we want them to be, and that can be dangerous.

Spencer Horn

06:02 - 06:51

for sure. That's right. And so, what's so interesting is just the quantity of information. And one of the things I wanted to share with our viewers, if they're able to see, is with different technologies, we can create Videos, I think there's a software tool called Hey Jen, where you can create basically avatars of yourself speaking in multiple languages. And it looks like it's, it's you, uh, you know, you're familiar with how interpretation services have, have progressed over the years. We no longer really need. interpreters. So you could have, you know, Christian, you're talking head interpreting in 10 different languages and it looks like it's you speaking those languages.

Spencer Horn

06:52 - 07:41

We can create images that are just not real. And so because of how our brains function and work, you know, images are powerful signals to us to believe in something or not. And, you know, I know that some of us think that we can identify fake images or not. I'm going to show you an example of this. I created an image through a software that actually helps you to create any kind of images that you want. Now I'm blanking on what it's called, but I used it. I'll think of it in a moment. Here's the image that I created, and I had to be very specific about how I did this.

Spencer Horn

07:41 - 07:52

I said, I want a six foot seven bald man with a pair of clear glasses. Do you know anybody that fits that description? I'm looking at him right now. Not the

Christian Napier

07:53 - 07:56

one that's illustrated.

Spencer Horn

07:57 - 08:32

Exactly. I said, I want a light coming from this direction. I want him to look serious and I want him to be climbing a mountain. And I had to really work at it because it got it wrong a lot. So I had to get very clear about what I wanted. The idea was I was going to then take a picture of myself, my head. and put it over top of this image so it looked like me. And I gave him the specifications, 285 pounds. I mean, that's a lot. And so this made me look nice and slim.

Spencer Horn

08:33 - 09:04

But then my friend Ernie Harker, who is an AI marketing genius and an artist, just took a picture off of social media and popped my head on it. Now, you can definitely tell that's not real. But we could take some more time and really get a picture of me with the right Angle and and the right lighting to fix this, you know to make this picture look like it's actually me climbing a cliff And you would have a hard time knowing if that was actually

Christian Napier

09:04 - 09:33

real Yeah, well one of the telltale signs at least now a eyes are getting better at this but one of the telltale signs of AI image is looking at hands if you notice the hands are that are grasping the side of the mountain. He's got five fingers, not including the thumb. His ring finger actually splits into two fingers. So you can look at that and say, ah, that was an AI generated image. It was not real. You see that?

Spencer Horn

09:34 - 09:37

His ring finger splits into two fingers.

Christian Napier

09:38 - 09:43

Yeah. Can you see that? So it looks like he's got five fingers holding onto the rock when in

Spencer Horn

09:43 - 09:44

fact

Christian Napier

09:44 - 10:08

he's got four. So generative AI images are still struggling to generate hands. Hands are very difficult for generative AI. And so one of the telltale signs is just look at the hands. If you see something weird going on with hands, it's got the wrong number of fingers, or doesn't have a thumb or something like that, then it's a pretty

Spencer Horn

10:08 - 10:10

clear... But when it figures it out, then we're really in trouble.

Christian Napier

10:12 - 10:50

Yeah, I mean, so that's what they're trying to do now, right? Is they're trying to improve the model so that they can get hands better. Because hands are very difficult for generative AI. And once they get that, then we're going to have to find something else that it kind of messes up with. But it takes a discerning eye, right? And that kind of comes to some of the points that were made in the article that you referenced. because you just give it a glance and it looks great. And that's the challenge with generative AI is it can generate very plausible but inaccurate responses, whether those are images or text.

Christian Napier

10:50 - 11:18

It can sound very confident in the information that it delivers. And so sometimes we just read things and we accept it at face value. Like, oh, that sounds reasonable. But you need to be a little bit more discerning, apply a little bit more critical thinking. And then you can start to poke holes in what AI is telling you. And that extends beyond just AI, but it's actually the messages that we all tell each other every day.

Spencer Horn

11:31 - 12:05

Well, we'll come back to this idea of critical thinking because that's one of the skills that we need to have to make sense of the noise, right? Let me just give you another fact about the noise that is out there. When, you know, we live in a world where there's just so much information, I think we can all agree. The problem is not enough information, it's too much information. And in 2015, the world created and consumed 16 zettabytes. Did I say that correctly? Or is it zettabytes?

Christian Napier

12:05 - 12:08

That's how I think it's supposed to be said. Yeah, zettabytes.

Spencer Horn

12:09 - 12:28

Can you tell our listeners what that is, if you even know? I didn't know. It's a trillion billion. Or a trillion gigabytes. It's a trillion gigabytes. So how many zettabytes are we awash in, in 2025? Oh, I don't have the article

Christian Napier

12:28 - 12:31

in front of me. 181. So in 10 years, we've gone from 16 zettabytes

Spencer Horn

12:32 - 13:41

to 181 zettabytes of data. We are swimming in data. And so what's really cool is that Gen AI has democratized information. It used to be that it was just the researchers and the analysts that had all the information, but now you and I can have access to so much information, which is a wonderful thing. The challenge is that the world is flooded with information. So as leaders, as project managers, as advisors, as anybody who is in a decision-making position or an advisory position, our challenge is understanding the information, bringing wisdom to the fight, if you will, and not just having data at our fingertips.

Spencer Horn

13:41 - 13:57

And there's a lot of reasons why information and data are not super helpful anyway. So as people in these different types of positions, we have to be very effective at getting rid of the noise. So how do we start to do that?

Christian Napier

13:59 - 14:45

Well, that is a challenging question, right? I would say, in my experience, you first have to put on some filters, right? One thing that you know, you learn is that you can absorb light from various wavelengths in the spectrum. And there's certain wavelengths that we can observe and others that we cannot. But you can apply filters to see light at certain wavelengths, right? You can have infrared, you know, night vision lenses that allow you to see things that you normally couldn't see. And on

Spencer Horn

14:45 - 14:45

the other

Christian Napier

14:45 - 15:24

side of the spectrum, you've got UV, things that allow you to see light in the ultraviolet spectrum and so on and so forth. So it's important, I think, to apply some lenses. In the case of teamwork, in my view, and this is just me riffing here, but in my view, those lenses are accuracy and relevance. So you've got to be able to have, and that's one of the great benefits of experience, right? If you have a lot of experience, you can tune out a lot of noise because you can say, hey, there's all this stuff happening.

Christian Napier

15:25 - 15:39

It's not relevant to what we're about. So we need to focus on the things that are relevant to us. And then we have to make sure that the information that we are getting that is potentially relevant to us is actually accurate.

Spencer Horn

15:40 - 16:13

So you just brought up a really interesting point. Think about all the young people that we're hiring today that feel like they're, because of the democratization of information, they feel like they're armed, if you will, to just go into any job and take over because of AI. You know, they can do all the research so quickly. They can, you know, search on YouTube. You know, they want your job immediately because they feel like, you know, they think they know just because they know how to how to find information. And you're saying that that's not enough.

Christian Napier

16:15 - 16:18

No, because there's, like you said, there's 181 zettabytes or

Spencer Horn

16:18 - 16:19

however many

Christian Napier

16:19 - 16:53

zettabytes of information out there. And the vast majority of it is not relevant to what we need to do in our specific organizations or our teams. And so we've got to develop relevancy filters that allow us to just kind of set aside the noise and focus on the things that really matter. For those things that really matter, we then need discernment so that we can determine whether what we're allowing to come through that filter is actually accurate.

Spencer Horn

16:53 - 17:36

So I love the metaphor, and that's actually one of the skills that we need to be able to have is to create metaphors in a way that help us understand something that we don't understand in a way by using a message of something that we do understand. And that's something that you just did. And it's interesting. The idea is you talk about filter. It's finding patterns. It's finding and synthesizing information so that you are finding maybe seemingly unrelated things and finding a way that they relate, connecting dots. I've got a

Christian Napier

17:36 - 17:39

question for you Spencer. I've got a question for you about this dot connecting.

Spencer Horn

17:40 - 17:40

Yeah,

Christian Napier

17:40 - 18:34

I'm really curious because you work with teams around the globe all the time and when it comes to connecting dots, you mentioned, hey, we need the ability to take potentially unrelated pieces of information, bring those together and synthesize something that is really, really helpful and meaningful. And one of the challenges I see organizations having is specialization, right? So in order for us to become super efficient and productive in our work, we specialize in a very certain thing, you know, narrow, narrow focus. And, and that could potentially hurt our organization's ability to connect these seemingly unrelated things.

Christian Napier

18:34 - 18:59

So I'm curious, in the work that you're doing with teams all around the world, How do you tackle this problem? We have to specialize because it helps us to be more productive, yet at the same time, we potentially limit opportunities for innovation because we, as an organization, we cannot connect those unrelated dots?

Spencer Horn

19:00 - 19:42

Yeah, that's a really good question. And, you know, you've heard of the idea of silos, right? Silos exist within organizations. That's where people are working in, if you will, echo chambers, or they're just, they're working in, I'm in the finance department, we're just focused on what's important to us, or I'm in the marketing department, or I'm operations, and so I work with leaders all the time to understand the tension that exists between different departments. So for example, let's say you've got an architectural firm, right? And so one department has to go out and sell their services to potential clients.

Spencer Horn

19:42 - 20:23

Let's just say that those are hospitals, right? And so they go out and they find all the hospitals that are doing rebuilds, that are doing expansions, and we're the architect firm for you and we have the capacity to do what you need us to do. Well, business and development or that sales department's job is to get as many of those opportunities for the company as possible. Well, the problem is that the design team is already at capacity. They have no more capacity to work more than 12 hours a day. They're already stretched. And so what happens is you've got one department that is pushing for greater sales and other departments saying, listen, we can't You're making promises that we can't keep.

Spencer Horn

20:23 - 20:58

You're making decisions that are impacting the company, specifically my department, where we're going to lose good people because we're turning over instead of getting together and having an effective conversation to figure that out. What's the solution? Is it cutting sales? Well, maybe that's not the best solution, but how do we expand our capacity to be able to keep up with the demand? What's the right combination? You cannot make decisions in in absentia of other departments. And so one of the ways to really do that effectively You know, we just saw our president have his first cabinet meeting.

Spencer Horn

20:58 - 21:34

That's bringing all the different department heads together and figure out how decisions that we're making are affecting every other department. And as an individual siloed department, how are your ideas that you're bringing to the table going to impact the people on your same team? And we need to be thinking about that as we go to those meetings, but we need to have effective meetings, Christian, where we actually are able to come to the table and recognize that there are natural tensions that exist between different departments. I just gave you an example, sales and operations, right?

Spencer Horn

21:34 - 22:11

I mean, we've got one team that has to implement the promises that are made by sales. Well, those are two different things, but they're both necessary to the success of the team. So how do we solve that tension in a way that is most beneficial to the entire team and not just to one or the other? And we don't get it right, bad things happen. So I have a client that actually lost their director of design for this very reason because there was just no resolution. It was just sell, sell, sell. And they're like, we can't keep up.

Spencer Horn

22:13 - 22:37

hurting the mental health of everybody on that team. And the director said, I'm out. I can't live in an environment like this where we're making promises that we can't keep and burning our people out and not caring about them. So that's an example of, you know, you've got all, we're making decisions without really understanding, using wisdom to figure out how to get people to come together. I don't know if I answered your question.

Christian Napier

22:38 - 23:15

Yeah, you did. I think it's interesting. Going back, way back into the early 90s when I was working in that power sports space, the motorcycle space, this was the common example that I would see. You had a motorcycle dealership that was primarily run on pen and paper, right? That's how they did things. And then you say, okay, we're gonna introduce this computer system in here, right? The owner says, well, we need to get a handle on things. You know, I have no visibility on anything. It was happening in my dealership because everything's done on pen and paper, right?

Christian Napier

23:15 - 24:04

So the owner goes and buys a system and says, okay, we're going to implement this system so that I can see what's going on in my dealership and I can make better decisions. What is not clearly understood at the time is that in some cases migrating from a pen and paper solution to a computerized solution can indeed have some negative efficiency impacts on certain people in the organization. How so? Well, let's take, for example, someone comes in and they want to order Brakes you know for their bike, and they so they come into the dealership.

Christian Napier

24:04 - 24:42

They go to the parts counter. They say hey do you have? your brakes for this year make model the Guy at the parts counter goes back looks around says no I don't think we don't have any but we could special order them for you. What's your name? Okay, so they just write it down like okay. Here's your name and they write it on a piece of paper and They take that piece of paper and they stick it somewhere and that's it. Well, then we bring in a computer terminal and we say, okay, now you're going to use a computer for this transaction.

Christian Napier

24:43 - 25:14

And you've got to get this information from the customer, their phone number, their name, their mailing address, and so on and so forth, ways to contact them, blah, blah, blah. And by the way, this is the part that they're looking for. And the person at the parts counter doing pen and paper is like, It takes me more time to put that thing in the computer than it did for me to write it on a piece of paper. I don't want to do that. I'd just rather write it down on a piece of paper. But what is the downstream impact?

Christian Napier

25:14 - 26:12

Well, the downstream impacts, if I just write it on a piece of paper, It's very difficult for my parts manager to manage the inventory when he's got a ton of papers floating around with special orders. And it's impossible for the owner of the company to see what's going on in the company. Like, yeah, how many things do we need to order today? How many transactions we do today? If everything's done on pen and paper. So we end up inconveniencing the parts clerk by making that person's job more inefficient The betterment of the entire organization and the parts clerk gets mad because they're like hey, you just made my job harder I thought when we got computers my job was supposed to be easier like you guys are screwing me over and that happens a lot of time in organizations when leaders have to make hard choices and And they were going to have to inconvenience certain parts of the organization for the betterment of the entire organization.

Christian Napier

26:13 - 26:26

And that can lead to that tension for sure. However, if the people are made to, you know, if you clearly communicate, this is why we're doing this, and we know this

Spencer Horn

26:26 - 26:27

could have

Christian Napier

26:27 - 26:45

an impact, it could have an adverse impact on your part of the organization. and we feel for you in that case, but it will help our organization as a whole grow and eventually that will help your team. in the end as well as we

Spencer Horn

26:45 - 27:16

all. So you just gave a great example of, of, of dot connecting. And that is, we've got to really create what's called shared understanding in an organization. So if you're listening to this and you want to say, okay, we've got all this data, all this information out there. How do you get everybody on board? You have to be really good at sending the message of why we're doing this. I just went through a strategic planning session with one of my clients, and they thought they were very clear about what it is that they were doing.

Spencer Horn

27:16 - 27:54

Now, the challenge was that they were going through a merger. They brought in two other companies to be part of theirs because their strategic plan was to transition from a certain way of doing business to a new way of doing business. Not necessarily different businesses, although they're bringing on more services that are complementary to what they do. Yet how they were doing business was going to change. And I'll give you an example of just one seemingly simple thing. One of the services, what do we do? Snow removal. Well, just that word of snow removal was, you think you know what that means, right?

Spencer Horn

27:57 - 28:27

as a company, as a consumer, as a listener. But snow removal could be interpreted that you're going to remove all snow from our property all the time. And if you don't do it, if you just push it into a corner, that's not really snow removal, right? So are you going to take all of that snow and take it somewhere else and remove it from the property? No, that's not their model. And in some cases, that's what may be expected. And so they got very clear. They understand. So we're really in what's called snow and ice management.

Spencer Horn

28:29 - 29:10

We're not in snow removal. And something so simple as that is we're able now to get everybody on board about what it is we do, how we do it, because that then will will impact how we interact with the client and their expectations about how it is that we're going to manage the snow and ice in a way that is cost-effective for the client and a way that we can make a reasonable profit at so that we can continue to provide good service and value. Sounds so basic and so simple, but it requires an amount of wisdom that we need to have to say, okay, well, we think we know what we do, but We need to get clear about how we do what we do.

Spencer Horn

29:10 - 29:45

What are our values? What are the opportunities that we have? Do the opportunities that are presented to us actually fit our business model? Because there's so many things that we could do, it requires discipline and what you call the filter to get rid of things that are not important. So the first step is, Teams thrive when there's a shared understanding of what it is that we're doing, what opportunities we're taking advantage of, why we're doing this upgrade to computer systems, how it's going to impact everybody and not just you. Because it can't be about the name on the back of your jersey.

Spencer Horn

29:45 - 30:04

It has to be about the name of the entire team that you're on and not just how it impacts you. And so that's one of the ways that we get rid of silos when we start to create a culture where this is an entire team and not just me as department of X, Y, and Z, department head.

Christian Napier

30:04 - 30:46

So two quick thoughts on that. Number one, language and terminology is absolutely key to developing this shared understanding. We all need to have the same understanding of the words that we use. Yes. in the language that we use when we talk to our customers, when we talk to each other. We all have a common understanding of the terminology of the business. I think that's really, really important. The second point that before we started broadcasting here today that you brought up is the power of storytelling and developing this shared understanding because It's not just about facts.

Christian Napier

30:47 - 31:04

And when you start sharing stories and experiences, your teams can actually start to connect on a neurological and an emotional level, which can have an even greater impact, I think, on team performance.

Spencer Horn

31:04 - 31:28

So this is a skill, Christian, that is absolutely necessary to reduce the noise. You've got to be able to be really good at creating metaphors. Metaphors are very, very powerful. They help us understand things very, very quickly. In your opinion, do you think the ability to tell stories or to use metaphors is a skill that is growing or atrophying or diminishing right now?

Christian Napier

31:30 - 32:04

That's a really great question. I don't know if the skill is growing or diminishing, because storytelling for human beings is a pretty natural thing. That's how we learn from being babies. We learn from our own experiences, and we hear our parents read us stories at bedtime. And we learn a lot through stories. It's a natural way of communicating. I think, I'm just completely speculating. I don't know the answer to the

Spencer Horn

32:05 - 32:38

question. I actually think it's diminishing in the workplace. And I think part of the reason is, is the technology. We are becoming lazier. We are not becoming, we're not challenging our thought process as much. We rely on our technology and the tools that we use. We rely on generative AI to give us all this information. We're saying, okay, I've got to be more efficient, more effective. We're going to come back to that in a minute. And so we're trying to go faster and faster and faster. And stories actually require us to slow down and to think and to create analogies and create understanding.

Spencer Horn

32:38 - 33:13

I mean, it's one thing to be able to look in the sky and point out all the stars. It's another to be able to point out constellations and how different dots are related to create images that people can understand. And so that's our opportunity is, I mean, I'm just talking to a potentially new client, Christian, and one of the things they do is they do a corporate meeting every six months. And they're having department heads stand up and deliver information. And they're failing at it because they're just, first of all, they don't know how to tell stories.

Spencer Horn

33:14 - 33:52

And for whatever reason, they probably do when they're out on the job just about their personal lives. But when it comes to telling the corporate story and what it is that we're doing, they struggle and they fail. And so the meeting turns into a disaster. It's not motivating. They missed an opportunity to really get everybody on the same page and aligned because they want their people to get better at telling stories. They actually want to hire me to train their people. to be able to be better at creating stories and metaphors. So it's a problem that organizations are having, I think, more and more.

Spencer Horn

33:52 - 34:29

I've talked to people in the military that say as soon as a department implements an efficiency-creating technology, all of a sudden our skills begin to atrophy. Text has caused us to be able to Reduce our ability to communicate effectively because you got kids today that that can't think in more than you know 15-second memes or short texts or Acronyms, you know, whatever it is that they're using they they're struggling with having Cogent thoughts and and storytelling we I think those skills are actually atrophying. I

Christian Napier

34:31 - 35:06

You may very well be right, and I think one reason for that that I just see in business today is a real emphasis on evidence. So what we do is we put together a lot of numbers, statistics. We use numbers to try to make sense of all the information that we're getting. So what do companies do? They try to build a lot of dashboards. If I had a dashboard for this, I could see at a glance how my company's doing. And I could see red, yellow, green, or high, medium, low, or whatever it is. And I could see these dashboards.

Christian Napier

35:06 - 35:41

But what happens is dashboards are very poor at communicating context. Stories can provide context, metaphor can provide context, and so it becomes, certainly it's, you know, dashboards are not persuasive tools, right? They're just used to, okay, get information at a glance, but it's hard to persuade somebody to take a course of action based on the information that's provided in the dashboard if you can't provide the context. And the way you provide the context, and you make it really stick, is by sharing a story.

Spencer Horn

35:42 - 36:38

Yeah, and so that's one of the things that, so I got a couple of examples that I wanted to share with you. This might be a little, There's a way to create ideas very, very quickly. And in the United States, the political environment is very divisive, and it has been for a long time. But some of the different parties create metaphors by naming their opposition certain names. I'm going to give you some examples. And this is a way of telling a story. It's a metaphor. And very quickly, somebody is called, for example, I know this might be controversial, but somebody is called Governor New Scum, or somebody is called Crooked Joe or Sleepy Joe, or somebody is called a Nazi, or somebody is called a Hitler, or somebody is called crazy.

Spencer Horn

36:38 - 37:18

We assign something to create a story based on our narrative. And we have to be very, very careful about that because those stories are very powerful. Now, there's actually a study that was done by the University of Indiana that says those name callings, it doesn't work because most people see through them, which is very, very good. We have to be able to be very good at telling a story that hopefully we have thought about that is telling truth. Now, that's part, so I'm gonna, I'm jumping all over the place. That means we have to think critically about what we believe.

Spencer Horn

37:19 - 37:53

We need to challenge our own assumptions about what we believe because we live in a world where we're getting information that just feeds back what we want. I don't care what you believe. You can find a source or a reference that supports what you believe. That's called confirmation bias, right? And so we have a world right now that is so divided because so much information out there is available to you that supports your belief. So one of the skills that we need to have in this era of so much information is the ability to challenge our assumptions and each other's assumptions.

Spencer Horn

37:53 - 38:37

So one of the ways that we do that, that I'm going to suggest to you, is to invite disagreement. And disagreement can be threatening to some people. It's actually very, very helpful. So I'll give you an example. A leader says, I think we need to do this. I think we need to change our business model from X to, let's say, a subscription-based model. And everyone's, yeah, yeah, yeah. And he's like, OK, wait a minute. Before we make that decision, I need to hear why that's a bad idea. Somebody needs to tell me why this is potentially a bad idea and a risk so that we can hear things that we probably didn't think about that will make us more prepared for making that decision.

Spencer Horn

38:37 - 38:38

What say you?

Christian Napier

38:40 - 38:51

Yeah. Know we were so I just had this thought and again. I'm riffing here Spencer. I apologize I just had this thought because bringing it back to AI right

Spencer Horn

38:52 - 38:52

yeah, so

Christian Napier

38:53 - 39:02

so The idea of having different ideas from different areas not just getting siloed in getting a succumbing to the group think

Spencer Horn

39:02 - 39:03

yeah,

Christian Napier

39:03 - 39:25

this is not just a problem for human beings and This is a problem for AI. 100%. So one of the techniques that scientists use to train AI is something known as generative adversarial network. I don't know if you've heard this term.

Spencer Horn

39:26 - 39:27

I have not. Basically,

Christian Napier

39:27 - 39:27

what

Spencer Horn

39:27 - 39:27

they

Christian Napier

39:27 - 40:03

do, what the scientists do, is they pit two eyes against each other. They'll have one be the generator, and the other being the discriminator, right? So let's say that the AI is supposed to generate images of cats. So the generator has this task. I generate images of cats. The discriminator tries to poke holes in it and say, that's not an image of a cat because of X, Y, Z. And they have these generative adversarial networks. They just iterate, you know, thousands of millions and billions of times.

Spencer Horn

40:03 - 40:06

Does the generator get its feelings hurt?

Christian Napier

40:08 - 40:23

Well, if you believe they have feelings, but the whole point of it is, is to have two engines oppose each other. For what purpose? To learn, right?

Spencer Horn

40:23 - 40:24

To create a better

Christian Napier

40:24 - 40:40

outcome. To create a better, more accurate outcome. And, you know, why not do that in the human sphere, right? 100%. Create a generative adversarial network. It can be friendly, right? So we don't have to get our feelings hurt.

Spencer Horn

40:40 - 40:42

No, there's a difference between.

Christian Napier

40:42 - 40:53

To help, you know, to discriminate against whatever this other person is saying and, you know, get that back and forth going so that the organization can learn.

Spencer Horn

40:53 - 41:31

So the name calling that I described to you is what's called affective conflict, right? It's personal. What you're talking about is cognitive conflict, and that's the friendly kind. We want to have disagreement on ideas, not on personality, not on who you are as a person. You and I, Christian, disagree about things occasionally, but we're friends, and I value your opinion so much that I want to listen to it and hear more, and we need that. We need those differences. There's a lot of discussion in the United States today diversity and is it important or is it not?

Spencer Horn

41:31 - 42:16

I think this is exactly a reason for diversity. That's why you want to pit those computers against each other because you want to have different perspectives. Now, does that take longer? Yes, but actually it doesn't take longer because if you just go with the generative AI, you create an outcome that is not optimal and you're going to have to correct that eventually. So why not have the ability to think critically in the first place? I spend a lot of time working with executives, Christian, on how to be more productive. They come to me, they're frustrated that their teams aren't producing, that they're not being accountable, and I have to tell them, these leaders all the time, you're the reason why this is happening.

Spencer Horn

42:16 - 42:56

Because you're so busy being efficient, you end up taking on more and more responsibility. You get more and more frustrated with your people and you're not letting go of those responsibilities, but more importantly, you're not slowing down enough to actually take the time to coach and train and develop your people, help them develop those critical thinking skills, help them develop the experience that you've talked about. We need to be able to take more time with our people, not less. And so we think, well, I don't have time. I'm so busy getting everything done. And as a result, we're taking more time correcting all the mistakes that are being done.

Spencer Horn

42:56 - 43:42

We have burnout being created because leaders are doing more of their people's work. The people become disengaged because they're not trusted or given opportunities. When we slow down, When we challenge our assumptions, when we start taking time to really coach and develop our people, we'll be more effective, which in the long run will be more efficient. The problem is, is that we're worried about you know, the next hour, what we're doing instead of next week or next year. And it all adds up if we, if we just aren't, if we're just so busy making decisions and we're putting a question in the chat GPT and not even questioning the answers that we're getting from our technology.

Spencer Horn

43:43 - 44:15

We actually need to be that discriminator with the answers that we're getting. So I'll give you an example. So I used AI over the weekend to do something for me. I was listening to a lecture of Dan Clark, who's a Hall of Fame speaker. He spent almost the entire day talking about storytelling. And it was a lot. We didn't video it, but I recorded it on my phone. I took that recording and uploaded it to a transcript service, which is an AI, listens to it, transcribes it into little chunks, just like I do for our podcast here.

Spencer Horn

44:16 - 44:48

And then I took that and uploaded that into ChatGPT and said, I want you to summarize everything, which you did a great job of. But one of the interactions, Christian, was me talking to Dan about one of my stories that I wanted to improve. And I was giving him an example of how I was telling a sad story. and how I wanted to be able to pull the audience out of that by some comedy, you know, some relief. And I shared the story that I use and AI told me that my idea was really great.

Spencer Horn

44:48 - 45:15

And it was like, it was affirming message, Christian. It was like, oh, you know, your idea is good because of this. And I go, yeah, I need it to be better. And so today, I said, I want you to challenge the fact that you said that's a good idea. How can I make it better? Criticize that. Tell me why it's not a good idea. And I asked that question of ChatGPT. So we have to be better at critical thinking to make sense of the noise.

Christian Napier

45:18 - 45:57

I agree. And that's not easy. Because our friend, Dr. Paul Jenkins, likes to say our brain has two purposes, to keep us safe and prove us right, right? That's what we do. And so we feel good. Our brain feels good when it achieves those two purposes. And when it comes to this critical thinking, you have to open yourself up to say, you know what? I could be wrong. And viscerally, that's hard. That's why we like to just hang around with people that are like us, because it makes us feel good about ourselves. And so opening us up to that, it's a vulnerability.

Christian Napier

45:57 - 46:15

And we hear leaders talk all the time, we need to get out of our comfort zone. Well, that's what it means to get out of your comfort zone, is to be willing to open yourself up to the fact that you might be wrong. And that's hard. I mean, it's not natural. For us to want to do that. Well.

Spencer Horn

46:15 - 46:15

That's why I don't

Christian Napier

46:15 - 46:49

see the computers can make it a little bit easier You know it's like okay well if I ask chat GPT or Gemini or Claude or one of these things To assess what I'm doing to find weaknesses in my arguments to help improve what I'm doing I know that I'm interacting with a machine and I It doesn't sting quite as much as if I have an actual person tell me. And on the flip side, you know, sometimes when you're asked the question, what can I do better? It's hard for us to respond because we don't want to offend someone and hurt their feelings.

Christian Napier

46:49 - 46:50

And so we might just kind of...

Spencer Horn

46:50 - 46:52

No, Christian, you don't want to hurt the whole thing.

Christian Napier

46:52 - 46:52

I don't

Spencer Horn

46:53 - 46:54

care about hurting people's

Christian Napier

46:54 - 46:54

feelings.

Spencer Horn

46:57 - 46:58

Okay. Well, maybe

Christian Napier

46:58 - 46:59

that's you. No,

Spencer Horn

47:00 - 47:39

I do care. I do care. I care less than you do though. I do care, but that's part of it. Part of that is our personality. Some people are okay hurting people's feelings, and so we need to challenge that as well. I had to work hard to not, to ask a question in a way that is not shutting people down, but inviting people. to give me their open feedback because as a leader of an organization, I was not good at one point in my career at getting feedback. As a matter of fact, I thought that disagreement was a lack of teamwork, right?

Spencer Horn

47:39 - 48:21

You see those pictures of teams that are like rowing on a river. We're all wearing those uniforms and they're all floating down this river and they're rowing together. That's not how a team looks. you're bumping oars, waves are coming over the boat. We're not always smooth in how we are aligned together. And so I would shut down dissent. And that's exactly opposite of what we do. And there's a lot of leaders around the world that have those same personality traits that I do, which are toxic to really this critical thinking. Because they're like, this is the way it's gonna be.

Spencer Horn

48:21 - 49:00

I'm the leader, you're gonna follow, you're gonna get in line, or you're not a team player. If we create an environment where, yes, at some point a decision has to be made, where we make it safe, and invite people to challenge our thinking, you'll be better as a leader because you're going to have more information that is going to help you make better decisions. But now let's get back to how do we reduce the noise? So we've talked about a couple of things. We want to be very clear about creating understanding, connecting dots, simplifying, using filters, being really good at being clear about what it is that we want to accomplish.

Spencer Horn

49:01 - 49:18

Critical thinking prevents groupthink, which is something that happens even with AI because it's giving us information that we already want. So one of the suggestions that you have to prevent groupthink, why don't you share that? I mean, it's one of the things that you can ask AI to do is provide what?

Christian Napier

49:20 - 49:25

Oh, you can ask the AI, like we were talking about, to provide critical feedback, constructive critical feedback, right?

Spencer Horn

49:25 - 49:27

Yes, and also cite their sources.

Christian Napier

49:28 - 50:18

Oh, yeah. Of course, yeah. That kind of goes back to the accuracy of information. If you don't ask the AI to cite your sources or cite its sources, then it becomes easier to believe what it's saying. So if you ask it to cite its sources, it's very simple to click on the source and like, OK, I can do a check. I can sanity check what the AI is saying. And depending on the task, it may take a bit of time, and you might think, well, I'm just wasting my time. But in the end, you'll be much better off for it, as opposed to that famous case that happened, I think it was in New York, where the attorney used AI, and AI cited a bunch of fake cases that it made up, and the attorney didn't fact check and ended up suffering the consequences of that.

Christian Napier

50:19 - 50:25

So anyway, I think that's really important. I'm just looking at the clock here. We've got just a couple

Spencer Horn

50:25 - 51:17

of minutes here Spencer. So next we've got to get really good at storytelling so that we can be persuasive. That's the ability to use metaphors. That's a skill that you've got to develop. So dot connecting, critical thinking, metaphors, and really get good at synthesizing information. That's part of the dot connection. Wisdom is really more important than information overload. And that's about slowing down, taking the time to slow down, to really figure out what is true and what is not. And we're trying to use this generative AI to be more efficient and we're struggling. And that's one of the things I think it's really important for us to do is let's be more effective and less worried about efficiency.

Spencer Horn

51:18 - 51:24

And ultimately, I say we'll be more efficient. Last thoughts to you, Christian.

Christian Napier

51:24 - 52:00

Just on that last point. So my mother was an artist. Well, she's still alive. She doesn't really do art anymore. But she would always say, you know, she would do an illustration or a painting or something like that. And then rather than just say, OK, it's done, she would let it sit there for a couple of days and then come back to it. And then she would notice things like, oh, we could do this or we could do that. Sometimes when you're in the moment, it's hard to have clear judgment. So your point about slowing down is really, really relevant.

Christian Napier

52:01 - 52:08

Sometimes you need to take a day or two and step away from something and then come back to it with fresh eyes.

Spencer Horn

52:09 - 52:31

Can I just give an example of that with the strategic plan that we did? So we had a date and we came up with the main plan and then we came back two weeks later and then we're letting that sit for a month. We have some assignments and then we're going to come back and then have the final. You do need time to percolate and to analyze. That's such an important point, Christian.

Christian Napier

52:33 - 52:49

So a great conversation, Spencer, we could go on for hours about this topic. It's near and dear to me. You've helped so many organizations over time. Any final thoughts that you'd have to those who you're helping or who might be listening?

Spencer Horn

52:51 - 53:15

You know, I'd love them to listen to other podcasts that we've got a lot of great episodes. Go back into our library and subscribe to our teamwork podcast. Christian and I have had some great guests and great conversations. Look me up on LinkedIn, Spencer Horn on LinkedIn. And Christian, how can people get a hold of you as busy as you are? Oh,

Christian Napier

53:16 - 53:17

LinkedIn, same. Yeah, just

Spencer Horn

53:17 - 53:17

find

Christian Napier

53:17 - 53:33

me on LinkedIn. So, fantastic, Spencer. It's harder and harder to find dates to do these podcasts because you're so busy helping other people, Spencer. So, listeners and viewers, we're grateful for your patience waiting for new podcasts to come

Spencer Horn

53:33 - 53:36

out. Hey, we have a guest coming up on the 14th, don't we?

Christian Napier

53:36 - 53:37

We do, we do. Why don't you talk

Spencer Horn

53:38 - 54:17

about that? Oh my gosh, we have Amy Clymer, who is absolutely incredible. So Amy is going to be on the 14th, and she has just written a book that is hitting everything by storm. Top bestseller right now. She's Dr. Amy Clymer, and her book is Deliberative Creative Teams. And she's gonna talk to us about how to lead innovation in teams, three elements that all teams need to be creative. practical tools and techniques for developing new solutions with innovative results. She is so much fun to listen to. She's a great speaker, and she's going to join us in a couple of weeks live.

Spencer Horn

54:17 - 54:23

And then we've got another great guest after that in two weeks. So stay tuned. We'll talk to you about our next episodes.

Christian Napier

54:23 - 54:30

All right. Fantastic. Thank you, listeners, viewers. Subscribe, like our podcast. We'll catch you again soon on the 14th with Amy.